Chelsea Komschlies on Music, Color, and Neuro-Symbolism

As composers, we’re often asked to describe our music, and ironically, it’s one of the hardest questions to answer. What is a style, really? Many of us are still figuring out what our music sounds like, what connects our different projects, and how, or whether, that should be put into words.

For years, I’ve been fascinated by the Symbolist movement, especially in visual art. Symbolism emerged in the late 19th century as a reaction against realism, naturalism, and the idea that art’s job was to describe the external world as clearly as possible. Instead, Symbolist artists and writers turned inward, toward dreams, intuition, memory, spirituality, and states of perception that hovered just beyond ordinary language.

The name Symbolism can be misleading. This isn’t symbolism in the sense of allegory or codes to decode, or “X represents Y.” Rather, Symbolist artists believed that meaning could be suggested rather than stated. Through atmosphere, ambiguity, and the blending of the senses, art could gesture toward deeper truths, offering brief glimpses of something the artist might not even be able to articulate themselves.

Symbolists were drawn to what we might now call altered states of perception: dreamlike reverie, mystical experience, intoxication, obsession, ecstasy. They were interested in moments when perception loosens, when sensation, emotion, and imagination blur together. Sensory boundaries softened. Sound could feel like color; images could feel musical; meaning could arrive as a feeling rather than an idea. Baudelaire’s notion of correspondences, the echoing of one sense inside another, sits at the heart of this.

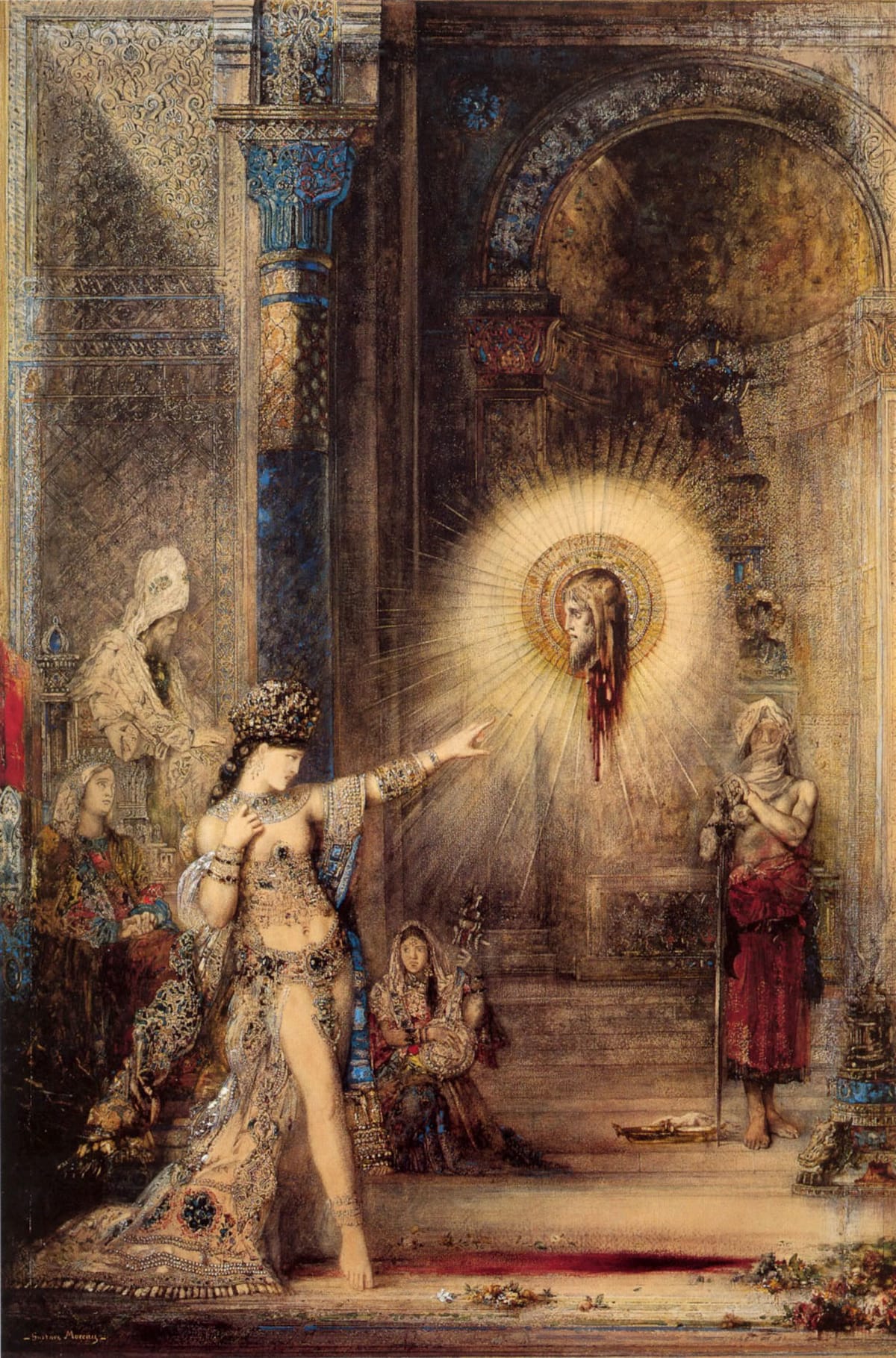

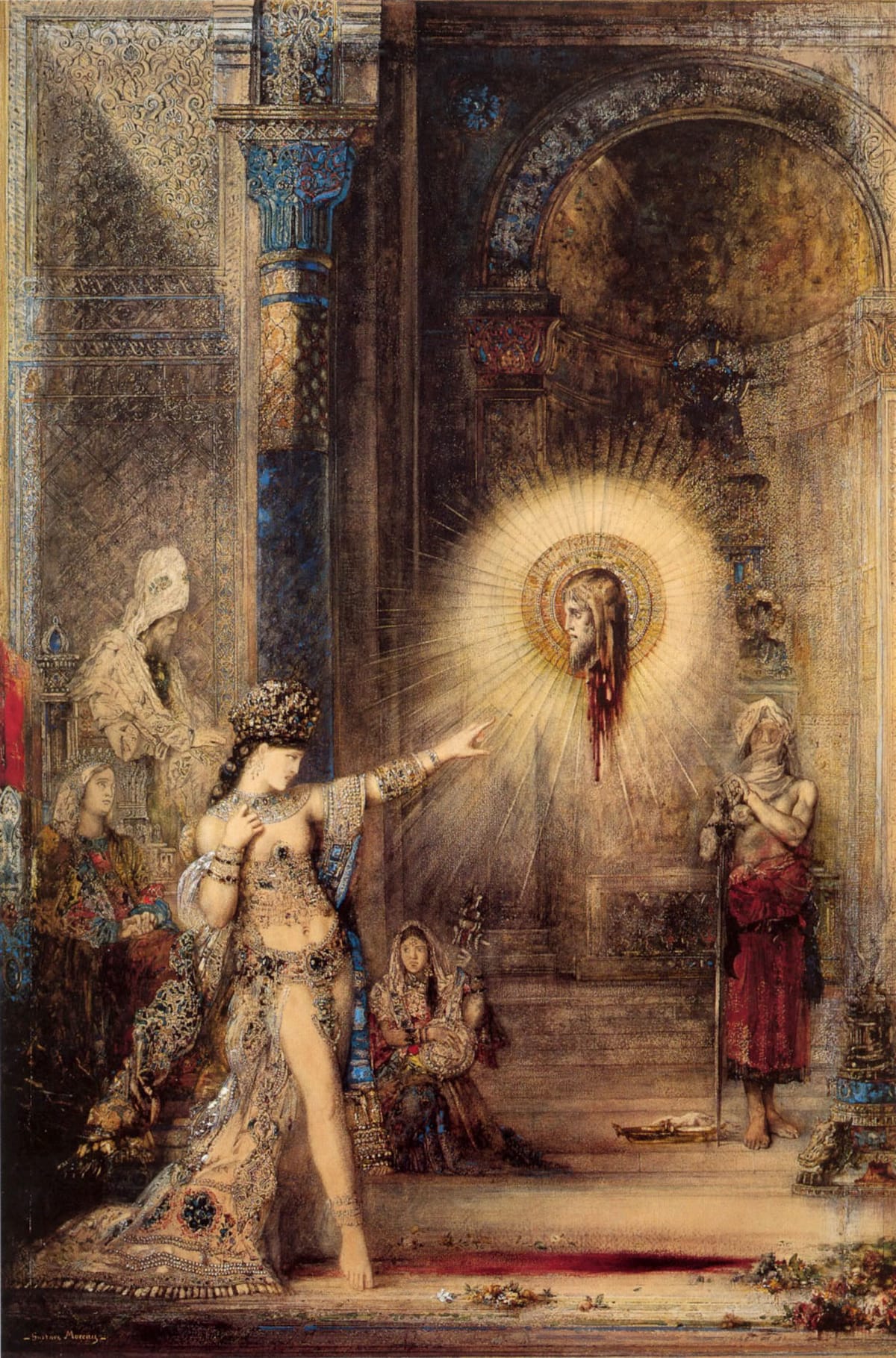

Visually and poetically, Symbolist work often feels ornate, exaggerated, jewel-toned, and dreamlike. There’s drama, sensuality, and a kind of charged strangeness to it, a “sexiness,” even, as if something inside the work is quietly alive. In the work of artists like Gustave Moreau, Jean Delville, Odilon Redon, and writers such as Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud, the power often lived in the aftereffect, the sense that something had passed through the mind, even if you couldn’t quite say what it was.

There were Symbolist composers too. Claude Debussy is often labeled an Impressionist, but in many ways Symbolism is a better fit, especially in his interest in suggestion, color, and atmosphere over formal declaration. Alexander Scriabin’s ecstatic mysticism and sensory thinking place him firmly in this lineage as well. Later composers like Olivier Messiaen, with his vivid inner worlds, synesthetic color thinking, and spiritual focus, also feel like inheritors of this impulse.

As someone whose mind works a bit differently than the norm, I feel a deep affinity with this tradition. I move easily into reverie states. I have synesthesia. I’m drawn to art and music that transports me, work that quiets my brain’s moment-to-moment, practical mode and opens something stranger and more expansive.

From a brain perspective, works like this seem to quiet the part of the mind that’s constantly narrating, judging, and problem-solving, and make more room for imagination, memory, and internally generated imagery. Neuroscientists often describe this shift in terms of the default mode network, which becomes more active when we daydream, reflect, or drift. When art is suggestive rather than literal, the brain isn’t just taking in information; it starts to participate, drawing on prior experience and expectation to shape what’s being perceived. This kind of top-down processing encourages the mind to wander, fill in gaps, and generate its own associations. I don’t pretend to know exactly what’s happening in the brain in these moments. I study crossmodal perception in my Ph.D. work, but when it comes to the full mystery of these experiences, I’m an enthusiast, not an expert.

I could describe my music as neo-Symbolist, and that would be accurate enough. Suggestion, sensory blending, spiritual curiosity, and glimpses of strange inner knowledge are central to my work. But I’ve been toying for a while with a play on that term, one that better reflects my compositional modus operandi: Neuro-Symbolist. By Neuro-Symbolism, I mean a continuation of the Symbolist tradition that’s also curious about how perception actually works in the brain. I’m interested not only in the ideals of Symbolism, but in the mechanisms underneath them. How sound, color, texture, and emotion intertwine in the nervous system. Why certain combinations of sensation feel uncanny, expansive, or meaningful across many different listeners.

Color plays a central role in this for me. I see my music in color, texture, temperature, and shape, but these aren’t private or arbitrary associations where a specific pitch “means” a specific color. They’re rooted in crossmodal correspondences that many people share: high sounds feeling bright or light, low sounds feeling dark or heavy, certain textures feeling warm, cool, metallic, or watery. This is perhaps why listeners often tell me they can see my music, even if they don’t have synesthesia themselves.

Ultimately, this connects to a long-standing question musicians love to ask: where does the piece actually live? Is it in the composer’s imagination? The printed score? The performance? For my own music, I’d take it one step further. The work isn’t complete until it reaches the listener’s mind. What matters most to me is the immediate reaction that happens there, the moment when perception shifts and an inner space opens that might not otherwise be reached.

Artworks in header:

1. Pinckney Marcius-Simons: The Grail (c. 1900)

2. Arnold Böcklin: Isle of the Dead, 3rd version (1883)

3. Pierre Amédée Marcel-Béronneau: Orpheus in Hades (1897)

4. Gustave Moreau: Salome and the Apparition of the Baptist's Head (1876)

-Chelsea Komschlies, Active Creator in Residence